It is well known that deep-fried Mars Bar is a Glaswegian chip shop staple, which may explain why Glasgow’s favourite fish restaurant has such a free hand with the butter.

Glasgow has a few fine fish restaurants vying for the title of favourite, as it ought to: there is so much fantastic seafood along this west coast of Scotland. I remember staying on the Isle of Mull and happening on a small mussel farm. The place was deserted, but they had a big cooler box filled with 2kg nets of mussels and an honesty box. It was £2.50 per net, I think. But we’re looking at something altogether more refined today, and so to Gamba, the self-confessed Glasgow favourite…

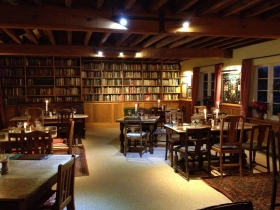

The restaurant is a cosy basement dining room, furnished with style and comfort. Stripey chair fabrics, an A-to-Z of fish on the wall, and plenty of space. Service was good, semi-formal and friendly. The bar at the front looked particularly snappy.

My starter was their signature fish soup, a delicious specimen with plenty of shredded crab in a satisfyingly deep fish stock, warmed by lots of ginger and coriander. This was the dish of the day, for me. Maureen’s tartare of sea bass included sesame oil, goat cheese and sun-dried tomatoes. An unusual concoction, more a cleverly forced marriage than a natural one. I would have expected the main ingredient to stand forward, but the fish was distinctly third fiddle.

For main I chose pan-fried hake with salsify, clams and toasted almonds. The whole almonds were a good addition, pebbles on my very seashore-looking plate. It was otherwise a classic, very well cooked, although I noticed belatedly that they’d left off the promised capers. A shame, as the acidity would have cut the lake of brown butter the dish swam in. I started off soaking this up with the handsome side-order of rooster chips but about half-way I could hear the faint squealing of my arteries hardening and left off.

The other side dish, a “fennel and orange salad”, was a disappointing mixed-leaf salad with unappealing vinaigrette and a few bits of fennel and orange. I’m not going mad. In this century the term “salad” doesn’t have to imply the inclusion of two handfuls assorted rabbit food, does it?

Maureen’s halibut was also swimming, and its ocean of cream and butter was even richer than mine. Beautiful piece of fish, again, and generous. The pieces of peat-smoked haddock with it were powerful good, presumably added to give some flavour punch although nothing was going to lighten the richness of the cream.

Although we both felt heavy with butter I tried a toasted caramel mousse for pud. The slight bitterness of the blow-torched surface was the only interesting taste in what was otherwise a butterscotch angel delight.

Gamba is for fish-lovers, and more particularly lovers of classic fish cuisine. These are generous portions of top-quality seafood, although some of the combinations on the plate seemed a little forced. I suppose we may have chosen the two richest dishes on the menu, but that isn’t how they read and I have to review what I ate. Prices are good for a high-end seafood restaurant, perhaps £38 per person for three courses without drinks. I wouldn’t argue for a special trip to Glasgow on the grounds of Gamba alone, but if you are staying in the city and wanting some classic seafood cooking then I’d point you here.